|

|||||||||||||||

|

Fritz Reuter was born in Stavenhagen, which was in the eastern part of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, on November 7, 1810. His father, Johann Reuter, was the mayor, registrar, and judge in this agricultural community which had a population of around 1,000.

Mecklenburg was full of green meadows, hundreds of lakes, and beautiful woods. A grove of thousand-year-old oaks grew in a park close to Stavenhagen. As a boy, Fritz was often left on his own, free to explore his small community or the surrounding countryside at will. Fritz did not go to school when he was young. He was taught at home by his invalid mother. She taught him to read and write, while his father taught him geography and mathematics. He also had private lessons from theological students who lived in Stavenhagen. Unfortunately Fritz was not given much discipline. His father was too busy with his own duties and responsibilities to supervise Fritz or Fritz's education. Following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Mecklenburg had a period of economic depression which lasted until the early 1820's. During this time, Johann Reuter was able to acquire extensive land holdings and at times provided work for as many as one hundred people. He introduced grains previously unknown in North Germany, built his own mill and brewery, and helped Stavenhagen survive the economic depression. Fritz's mother died in 1826 and his father shortly remarried. From 1824 until 1831 Fritz went to boarding school to prepare himself for university study. He was not interested in the courses and did not do well. Nevertheless, in 1831 he enrolled in law at the University of Rostock. Both law and the university were his father's choices, not Fritz's.. After one semester, he convinced his father to let him join his friends at the University of Jena. At Jena he quickly became involved in socializing, dueling, and drinking. He also joined the student society "Germania" which was a group of young students with liberal ideas of national unification and political freedom. As the political climate became charged in Germany, members of "Germania" held demonstrations and gave revolutionary speeches. Reuter did not become involved in any of these brawls or speeches, however, because violence was not a part of his nature. He did, however, wear the colors of the political organization. In early 1833 he left the University at Jena. Shortly thereafter, the government uncovered a plot that had originated at several universities, among them Jena, to overthrow the government. All the members of "Germania" were arrested or put on a "most wanted" list. Reuter was on the list, even though he was no longer at the university and had not participated. The fact that he was a member was enough. Fritz spent the summer in Mecklenburg where he was safe, but in October went to Berlin and was immediately arrested. In 1834 he was tried and found guilty of a crime against the Prussian state, and was sentenced to death. This sentence was then commuted to thirty years of fortress imprisonment. His father tried to get him extradited to Mecklenburg, but to no avail. It was not until August of 1840 that Reuter was finally released from prison through the general amnesty decreed by King Frederick William IV of Prussia. He returned home to Stavenhagen and later tried to go back to school in Heidelberg, but became a drunkard. His father looked on him as a hopeless failure and had him sent to his uncle's house in Jabel near Stavenhagen where he finally regained his health. In 1842 Fritz became a "Volontar" or apprentice without salary on the estate of Franz Rust at Demzin near Stavenhagen. He hoped to one day own his own land or at least become the manager or overseer of a large farm, possibly even a grand-ducal estate. He believed that his father was a wealthy man and that he would eventually inherit enough money to establish himself on his father's estate or elsewhere. When his father died in March, 1845, Fritz's dreams were shattered. His father's will left Fritz and his two half-sisters 4,750 talers each, but Fritz was to receive his share only if he was able to abstain from alcohol for a period of three years. Otherwise he was only to receive the interest on the capital and he was even to lose that if he were ever to marry.  His years in Demzin were

not wasted, however. He had the opportunity to make sketches of many people including farmers, teachers, preachers, merchants, farm laborers,

inspectors, schoolchildren, doctors, shepherds, and all the people who make up the population of a small Mecklenburg community and give it its special

character. He also became acquainted with members of the liberal bourgeois party who raised their voices in opposition to the noble landowners and the

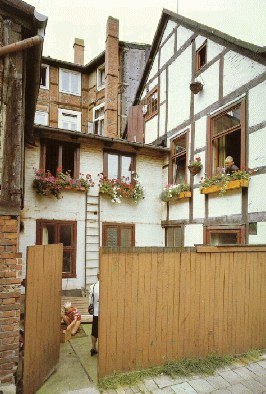

special privleges granted them. The house at the left was where Fritz Reuter stayed in 1848 while he was in Schwerin, meeting with friends from the

liberal bourgeois party and talking about the government and its possible reform. This movement and the lives of the common people later became the

impetus for Reuter's writings. His years in Demzin were

not wasted, however. He had the opportunity to make sketches of many people including farmers, teachers, preachers, merchants, farm laborers,

inspectors, schoolchildren, doctors, shepherds, and all the people who make up the population of a small Mecklenburg community and give it its special

character. He also became acquainted with members of the liberal bourgeois party who raised their voices in opposition to the noble landowners and the

special privleges granted them. The house at the left was where Fritz Reuter stayed in 1848 while he was in Schwerin, meeting with friends from the

liberal bourgeois party and talking about the government and its possible reform. This movement and the lives of the common people later became the

impetus for Reuter's writings.

He also met Luise Kuntze, a governess for a neighboring pastor, while in Demzin. She was to become his wife in 1851, after his half-sisters realized what a beneficial influence Luise would have on him and agreed that he should receive the interest due him in the amount of approximately 240 talers per year, even if they were to marry. Luise and Fritz Reuter moved to Treptow, Prussia where he became a Prussian citizen. This marked the beginning of Reuter's career as a writer of Plattdeutsch or Low German literature. In 1856, Reuter moved to Neubrandenburg, the largest and most important city in Mecklenburg-Strelitz at that time. Neubrandenburg had the advantage of publishing houses and book stores, both very important for an author, and a large circle of outstanding scholars including authorities in the field of Mecklenburg history. The seven years he spent in Neubrandenburg were the most productive of his entire life. By 1862 he was already a German author of renown. His works, because they were written in Plattdeutsch, were at first limited to Low German readers in North Germany, but by 1862 they were read in Upper Germany too. He was not only a literary success, but a financial success as well. He was happily married and found great satisfaction in his work. Reuter's longest and best known work,"Ut Mine Stromtid (My Years as a Farmer)" appeared in three volumes published over a period of 1862 to 1864. The enthusiastic reception given this novel by the public was almost without parallel for its time, and as a result, Reuter's name became known over much of the world. In Germany in the year 1906, more copies of "Ut mine Stromtid" were printed than of any other book. Before leaving Mecklenburg in 1853 to move to Thuringia, Reuter joined the newly founded National Association (Nationalverein), a liberal organization which was forbidden in Mecklenburg-Schwerin at that time. After moving to Thuringia, he began to realize how politically backward Mecklenburg was. Some agrarian reforms had been made, but the condition of the peasants on the manorial estates was still deplorable. Some improvement had also been made in city constitutions, but because city charters were based on different laws, utter chaos prevailed in this area too. Because of restrictive measures and also because of their own indolence, the Mecklenburgers, according to Reuter, had no political understanding whatsoever. There was policitical confusion in other German states too, however, and always the political activist, Reuter was moved to fight for national reform rather than just reform in Mecklenburg. Reuter lived to finally see the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. In a letter he wrote at that time, Reuter said, "I fell on my knees and thanked God that everything turned out so well. It has even turned out much better then we poor fellows ever dreamed of. As I now look back I see that everything we impetuous young students were unable to achieve at that time has now gradually come to pass after all." Fritz Reuter died on July 12, 1874. (Biographical Information taken from introduction to "Ut Mine Festungstid (Seven Years of My Life," written in 1861, English translation.) |

|||||||||||||||

|